|

Ten months earlier I had mentioned to my

dad that I was planning to go to Europe that summer and wanted to go to

Auschwitz. It was something I felt I should do, I explained, not only

to pay my respects to victims of the Nazi death camps, but because of

my religion. Though I am more culturally Jewish than religiously observant,

I had traveled in Israel three years earlier and came away from that trip

with an appreciation for my faith and my ancestors that years of religious

school had failed to instill. The next year, during a trip to Prague,

my sister and I went to Terezin; Auschwitz-Birkenau seemed like the logical,

albeit grim, next step.

My

father, a man who hates to fly and had not been overseas for nine years,

decided to accompany me; my mother had to work and couldn’t join

us. I was surprised but also excited by my father’s decision; he

and I generally got along incredibly well, and I was anticipating an interesting

trip. We decided to go to Poland first to get the hardest part over with,

and then spend the next ten days moving west through Prague, Paris, and

London. So there we were, kilometers away from the hardest part, and all

I felt was trepidation. Heading back to Krakow was looked like a viable

alternative all of a sudden. My trepidation was related not so much to

our destination but to my companion. I knew that touring Auschwitz-Birkenau

would be difficult, but I also knew that there was a limit to how much

I could prepare emotionally. At least, as far as seeing the actual camps

went. There was no way I could prepare myself, emotionally, intellectually

or otherwise, for the possibility that my father would fall apart. My

father, a man who hates to fly and had not been overseas for nine years,

decided to accompany me; my mother had to work and couldn’t join

us. I was surprised but also excited by my father’s decision; he

and I generally got along incredibly well, and I was anticipating an interesting

trip. We decided to go to Poland first to get the hardest part over with,

and then spend the next ten days moving west through Prague, Paris, and

London. So there we were, kilometers away from the hardest part, and all

I felt was trepidation. Heading back to Krakow was looked like a viable

alternative all of a sudden. My trepidation was related not so much to

our destination but to my companion. I knew that touring Auschwitz-Birkenau

would be difficult, but I also knew that there was a limit to how much

I could prepare emotionally. At least, as far as seeing the actual camps

went. There was no way I could prepare myself, emotionally, intellectually

or otherwise, for the possibility that my father would fall apart.

Through

ten months of planning for this trip, my father often mentioned that he

was worried about being unprepared, emotionally, to see the camps. He

had read just as much, if not more, Holocaust literature as me, and as

an avid student of history he knew the context and the statistics. This

knowledge seemed to reinforce, rather than alleviate, his sense of being

unprepared, and I was worried that seeing the tangible remainders of a

horrible event would be too much for him. My trips to Israel and Terezin

had given me some idea about how to handle the camps, but my father had

no such experiences to draw from. He just had his memories of living as

a child in Germany after World War Two, of the Anti-Semitism he had encountered

in the United States, and his knowledge that we were in a country where

so many of our faith, including relatives, had perished. Through

ten months of planning for this trip, my father often mentioned that he

was worried about being unprepared, emotionally, to see the camps. He

had read just as much, if not more, Holocaust literature as me, and as

an avid student of history he knew the context and the statistics. This

knowledge seemed to reinforce, rather than alleviate, his sense of being

unprepared, and I was worried that seeing the tangible remainders of a

horrible event would be too much for him. My trips to Israel and Terezin

had given me some idea about how to handle the camps, but my father had

no such experiences to draw from. He just had his memories of living as

a child in Germany after World War Two, of the Anti-Semitism he had encountered

in the United States, and his knowledge that we were in a country where

so many of our faith, including relatives, had perished.

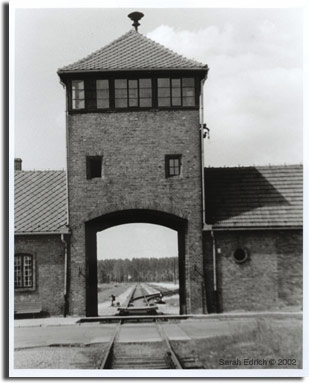

The

parking lot at Auschwitz was innocuous enough; the entry hall served as

both an information center and a small museum, which we walked through

quickly. As we stepped out into the courtyard, I was slightly ahead of

my father and did not see his expression as he took in the neatly swept

grounds. But I heard his gasp and turned quickly to see him standing stock-still,

hand over his mouth, eyes obscured by sunglasses. After that one intake

of breath, he seemed a statue. I didn’t know what to do; I wished

that my mom were there. The

parking lot at Auschwitz was innocuous enough; the entry hall served as

both an information center and a small museum, which we walked through

quickly. As we stepped out into the courtyard, I was slightly ahead of

my father and did not see his expression as he took in the neatly swept

grounds. But I heard his gasp and turned quickly to see him standing stock-still,

hand over his mouth, eyes obscured by sunglasses. After that one intake

of breath, he seemed a statue. I didn’t know what to do; I wished

that my mom were there.

“Are you OK?” I asked stupidly. “Do

you want to sit down?” My dad nodded, but then recovered himself.

If there were tears in his eyes I couldn’t tell, and I was glad

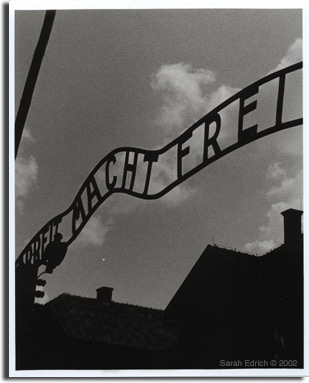

for that. We slowly passed under the infamous Arbeit Macht Frei (“work

is freeing”) sign that heralded the entrance to Auschwitz. We spent

the next several hours taking black and white pictures and lost in our

own thoughts.

My

impressions of the camps themselves are few. The sign was smaller than

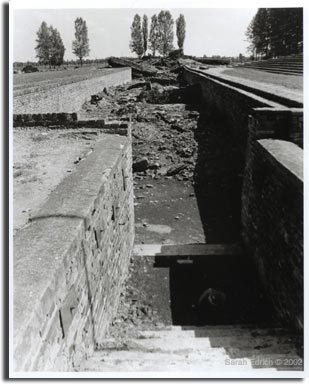

I imagined, the gas chambers were silent and eerie, and the small patch

of land where ashes of the victims lay was terrifyingly real. In those

hours, I could not go beyond surface impressions because I knew that if

I actually thought about what we were seeing and what it meant, I would

be the one to fall apart. All of my energy was focused on my father: walking

next to him, asking banal, historical questions, and listening to his

despairing comments about the loss of life and the nature of evil. If

I provided any support for him with my attention, he gave me just as much

by allowing me to step back from the horror of the past and concentrate

instead on the urgency of the present. My

impressions of the camps themselves are few. The sign was smaller than

I imagined, the gas chambers were silent and eerie, and the small patch

of land where ashes of the victims lay was terrifyingly real. In those

hours, I could not go beyond surface impressions because I knew that if

I actually thought about what we were seeing and what it meant, I would

be the one to fall apart. All of my energy was focused on my father: walking

next to him, asking banal, historical questions, and listening to his

despairing comments about the loss of life and the nature of evil. If

I provided any support for him with my attention, he gave me just as much

by allowing me to step back from the horror of the past and concentrate

instead on the urgency of the present.

- Sarah Erdreich

|